Light snow dusted the

cobbled streets of Paris as carriages pulled up to the Hotel

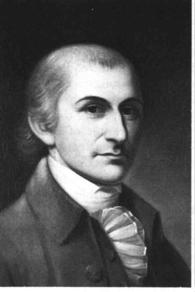

d'Orleans on the Rue des Petis-Augustines, where the American, John

Jay, had arranged to commence treaty negotiations with England on

October 30, 1782. (for more, click here)

This and subsequent

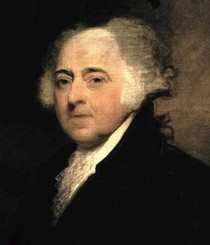

sessions commenced at 11 o'clock each morning. Negotiating

for the new republic were John Jay, John Adams (who had three weeks

before concluded a treaty of commerce with the Dutch at the Hauge),

and Benjamin Franklin, who represented the United States to the

French throughout the War of Independence.

As secretary

for the American commissioners, Franklin selected his grandson,

William Temple Franklin, the twenty-two year old illegitimate son

of Franklin's illegitimate son, William, the former Tory governor

of New Jersey who was then living in London. Also in

attendance were Franklin's longtime friend and associate, a British

spy named Bancroft, and the young French hero of the American

Revolution, the Marquis de Lafayette, recently arrived home from

North America.

(Click here for more on this treaty)

The fundamental

questions to be dealt with in the treaty negotiations were: the

boundaries of the United States; the right of navigation on the

Mississippi; debts; the interests of American Tories and Loyalists;

and American fishing rights on the Grand Banks off

Newfoundland.

The Americans insisted that Britain cede all territory

between the Appalachian Mountains on the east, and the Mississippi

River on the west. Britain agreed to this demand, "thus at a

stroke doubling the side of the new nation."

The preliminary

draft of the treaty was signed on November 30, 1782. Richard

Oswald, representing England, was first to sign, followed by the

four Americans.

The final

document would be signed at the Hotel d'York on the Rue

Jacob. Again, the signatures would be fixed in the customary

order, Adams, Franklin, Jay, along with that of the King's new

representative, David Hartley. The all important first

sentence of Article I declared "His Britannic Majesty acknowledges

the said United States…to be free, sovereign and independent

states." Then, the last line read "Done at Paris, this third

day of September, in the year of our Lord, one thousand seven

hundred and eighty three."

Just a few miles away, and some

twenty years later, another agreement would be struck that would

'change the known world' by more than doubling the geographic area

of the new nation. In the first treaty, Britain sought to

separate the Americans from their French allies. In the

second, France's Napoleon sought to separate Americans from their

British cousins.

The treaty at Paris was as

advantageous to Americans as any in history, and the American

negotiators were received at home as heroes.