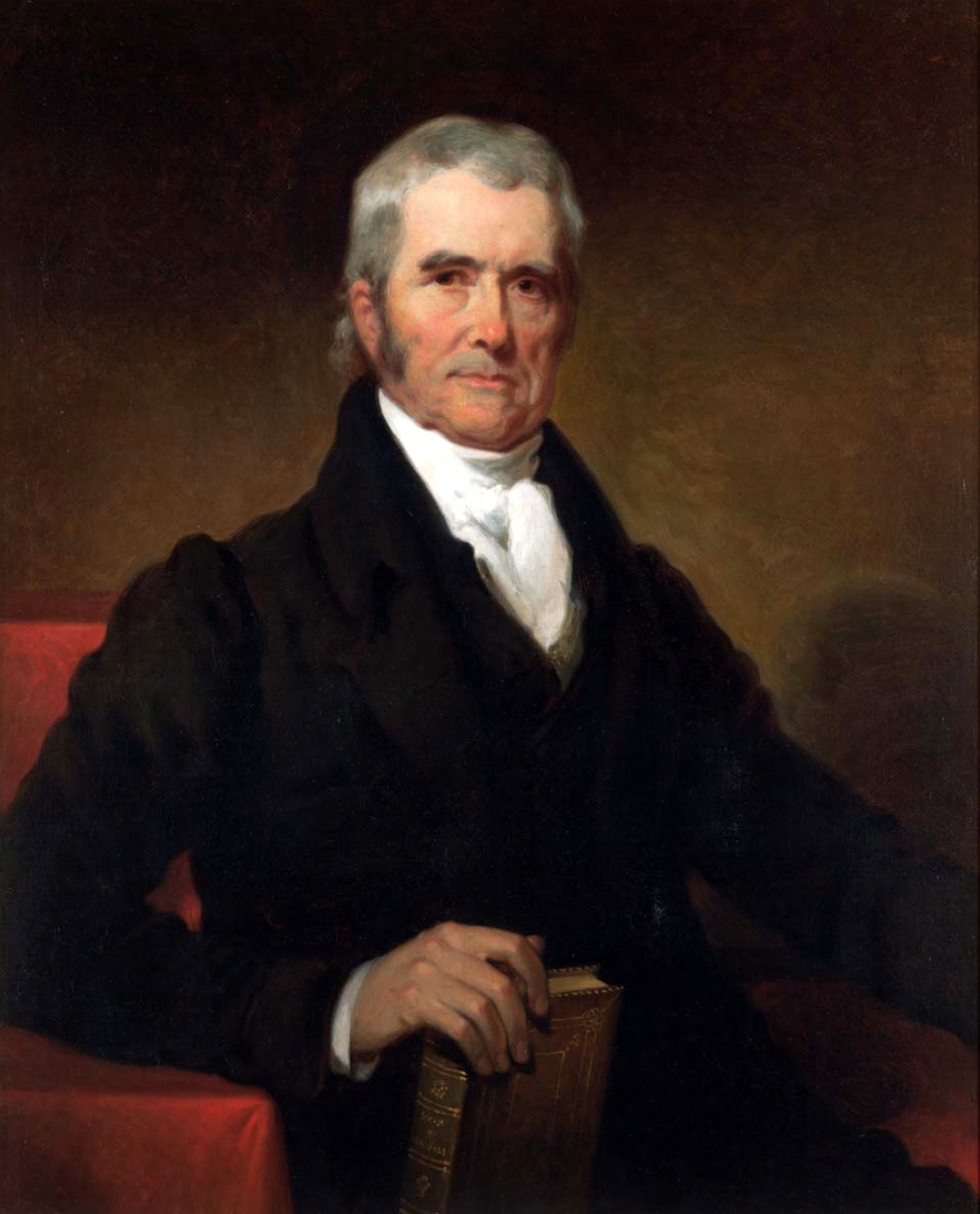

At the age of 45, the staunch federalist

John Marshall was nominated by President John Adams to become the

second chief justice of the U.S. Supreme Court. In many

respects, this nomination was revenge for Adam's bitter election

loss in 1800, as Adam's nemesis, Thomas Jefferson, would now be

bedeviled by the federalist viewpoints of his cousin, John

Marshall, throughout his presidency.

(Click here for more on Marshall)

Like his friend George Washington,

John Marshall had a thoroughgoing distrust of Jefferson's political

philosophy. Daniel Webster, the great jurist from the state of New

Hampshire, would later say of Marshall: "I have never known a man

of whose intellect I had a higher opinion." Marshall's

colleague on the high court, Justice Storey would write: "His

genius is, in my opinion, vigorous and powerful, less rapid than

discerning, and less vivid than uniform in its light...it unravels

the mysteries with irresistible acuteness. In subtle logic, he is

no unworthy disciple of David Hume..."

Marshall would write the majority

opinion in many landmark decisions that transformed the U.S.

Constitution from a document of words and lofty ideas into the

actual machinery of government. He was devoted to the

rights of property, to steady government by the educated, wealthy,

wise and good, and became the personification of the reaction

against popular government that followed the French

Revolution. Among his most profound beliefs was the

opinion that the common man, left to themselves, were incapable of

self-government.

Related People

Related Events

Related Flashpoints