The Doctrine of Discovery allowed European monarchs to lay claim to vast territories 'discovered' by their proxies, such as the conquistadors Pizzaro and Cortez.

The origins of

the Discovery Doctrine can be traced back to the Crusading-era

papacy of Innocent III and IV, in the thirteenth century (see

Innocent III in Faces). Two centuries later, Pope Nicholas V

gave a Portuguese king permission to claim lands his armies had

'discovered in Africa. Pope Alexander extended those same

territorial imperatives to Spain's King Ferdinand and Queen

Isabella in 1493, granting them the right to conquer lands and

peoples in the new world across the sea. Arguments between

Portugal and Spain led to a treaty which clarified that only

non-Christian lands could thus be taken, as well as drawing a line

of demarcation to allocate potential discoveries between the two

powers.

Though its origins were theocratic in nature, the Discovery

Doctrine became a settled concept of international law in the 16th

and 17th centuries. At that time, European monarchs claimed primacy

over lands owned by native people, but European governments began

disavowing this doctrine in the 18th century. The United

States, however, incorporated the legal tenets of the Discovery

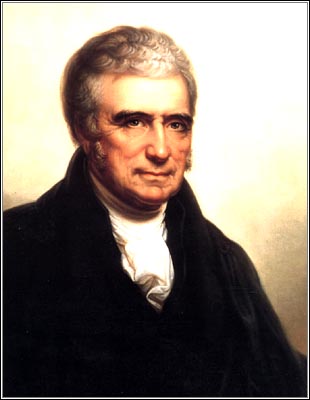

Doctrine into its founding principles. Chief Justice John

Marshall gave conditional support to those tenets in his opinion in

Johnson v McIntosh, in 1823. Nevertheless, ten years

later, in Worcester v. Georgia, he also ruled that Indian

nations were sovereign governmental entities retaining all of the

privileges accorded to nationhood.

click here for more on the discovery

doctrine

Related Events

Related Flashpoints