The most

serious problem affecting Indian/white relations on the Great

Plains in the 1860s grew out of the failure of the annuity system -

an invention of the Great White Father. This 'tangled

consequence' of failed promises resulted from the vast number of

treaties struck with roaming tribes (for the acquisition of land)

throughout the 1850s.

The government

obtained title to these lands through Indian land cessions and

thereby assumed an obligation to provide compensation to the tribes

in the form of annuities. Since a reduced land base for the

Indians drastically reshaped their ability to sustain themselves by

the chase, the annuities were a critical component to

survival.

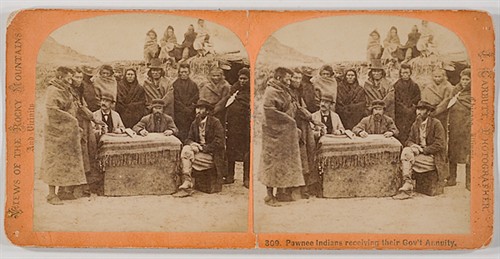

A stereopticon image of Pawnee Indians receiving

annuities guaranteed to them by treaty.

Following ratification of these

treaties by the U.S. Senate, the distribution of promised annuities

was the responsibility of officials of the Indian office.

Some historians have concluded that the tribes received no more

than half that was promised them. "The annuity system," wrote

Hiram Chittenden, 'probably gave rise to more abuses than any other

one thing in the conduct of Indian affairs."

In the summer

of 1864 as new wars broke out between whites and the plains tribes,

DeSmet saw the effects of this abuse first hand. As

explained by historian Hiram Chittenden, "The unhappy war

which is now raging so fiercely over all the extent of the Great

Desert, east of the Rocky Mountains, has, like so many other Indian

wars, been provoked by numerous injustices and misdeeds on the part

of the whites, and even of agents of the Government. For

years and years they have deceived the Indians with impunity in the

sale of their holdings of land, and afterward, by the embezzlement,

or rather the open theft, of immense sums paid them by the

government in exchange therefore."

S.J. Killoren

adds: "The sorry fact is that despite the ready promises given by

negotiators Mitchell and Fitzpatrick in 1851, Manypenny in 1853-54,

Cumming and Stevens in 1855, Carson, Bent, and agent Jesse

Leavenworth in 1865, the Indian Office made no plans and took no

steps to develop the capability of fulfilling such

commitments. There continued to be general disregard for the

1834 directive specifying on-site residence for each tribal agent,

who "shall not depart from the limits of his agency without

permission."

There were no

organized procedures for distributing annuities, and agents in

remote areas were without means of transportation, offices, or

abodes to store the annuities and supplies provided - this despite

the 1847 legislation which called for "Superintendents, agents, and

sub-agent" to be furnished with offices for the transaction of the

public business, and the agents and sub-agents with houses for

their residence."