With the

buffalo being driven to extinction by white guns, the Cheyenne and

Arapaho pushed back. Half a dozen violent encounters took

place between Indians and settlers on the Oregon Trail. The

federal government was not honoring its side of the Fort Laramie

treaty, and something had to be done or they would

perish.

click here for more

In Jefferson

Davis' last official act as secretary of war, he directed a

campaign against the Cheyenne in order to punish them for

hostilities against whites settlers. They must be

'"severely punished," said Davis, "and no trifling or partial

punishment will suffice."

By right of the treaty at

Horse Creek, the Cheyenne and Arapaho held title to the land

between the North Platte and the Arkansas rivers. In 1854,

the eastern boundary of their territory had crumbled under the

weight of settlers in the Kansas Territory, and the federal

government did nothing to protect their treaty rights. The

migration routes of the buffalo - across the central plains of

Kansas and Nebraska - was now broken in two by emigrant roads which

the buffalo would not cross. Their winter camping grounds on

the eastern slope of the Rockies had been taken over by gold

diggers. By 1859, more than 100,000 'fifty-niner's'

were in the Pike's Peak country.

At the

conclusion of the Horse Creek Treaty, Fitzpatrick predicted that

the freedom of the plains Indian would be vanquished by the white

man in one more lifetime. His prediction, only five years

old, was already coming to pass. Historian S.J. Killoren

wrote : "It was one of the most flagrant and serious violations of

the guarantees made to the Plains' tribes by the Fort Laramie

treaty. Moreover, the invasion of Indian country by settlers

was specifically prohibited by the Kansas/Nebraska Act of

1854. Also, where were the white troops to protect Indian

rights. And while this was a depredation far more excessive

than any Indian attack on an emigrant wagon train, it occasions no

government condemnation. The War department fielded no

expeditionary force to punish and remove the invaders and thus

maintain the promised peaceful coexistence. The Indian

office, with direct responsibility, never filed a single complaint

with the department of war, or petition Congress to enforce the

treaty conditions. The trader William Bent noted in 1859 that

the gold miners had quickly taken over choice Indian country and

brought " many causes of irritation" to the land's owners.

Now they were being pressed into a small territory that was beset

by the constant parade of emigrants from Texas, Kansas, and the

Platte, and bisected into even smaller segments by criss-crossing

roads."

Bent

foreshadowed things to come in his annual report to Washington: "A

smothered passion for revenge agitates these Indians, perpetually

fomented by the failure of food, the encircling encroachments of

the white population, and the exasperating sense of decay and

impending extinction with which they are surrounded."

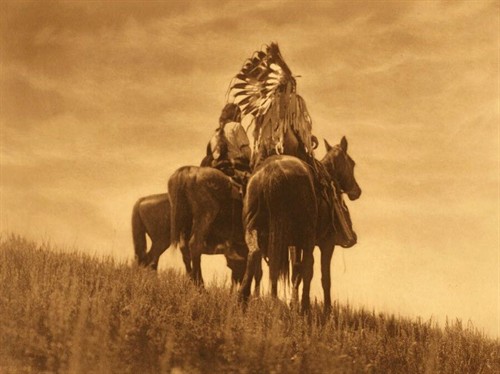

The days when

the nomadic tribes of the American West were the freest people to

walk the Earth, were quickly drawing to an end. These were

the first of the Plains tribes to experience this American tragedy,

and sadly, this grim and unyielding fate had become their legacy

from the lofty promises made to them at Horse Creek less than ten

years before.

In a footnote

to his commentary, Killoren writes that Agent Albert G. Boone,

Fitzpatrick's successor at the Platte River Agency, was directed by

Commissioner A.B. Greenwood to push the treaty signing with the

Cheyenne or "to make it over their heads." This new and

amended treaty was not ratified by the U.S. Senate until August 6,

1861. In the meantime, Kansas was admitted to the Union

without having title to the land. This was a violation of

both the Kansas/Nebraska Act, the treaty with France ceding

Louisiana to the U.S., and to the conditions of the treaty at Horse

Creek. No one in Congress raised a voice in protest.

Related People

Related Events

Related Flashpoints