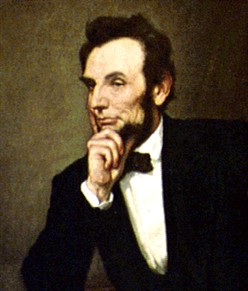

The Santee Sioux uprising in

Minnesota, ultimately put down by General Sibley, exposed

conflicting forces that were soon to erupt in violent conflicts on

the Great Plains. This uprising - as were most

uprisings - resulted from 1) a failure of the federal government to

make good on treaty promises; 2) a refusal to enforce restrictions

on an encroachment by white settlers, or 3) a combination of

both.

click here for more

The Santee

Sioux uprising in October of 1862 was a confrontation over treaty

rights (stemming from 'a combination of both') that President

Lincoln was ill prepared to manage from distant Washington.

Bureaucratic

delays in paying Indian annuities (see Annuity System

failures) lay at the heart of this conflict, as the destitute and

hungry Sioux faced starvation at the onset of winter. Their

agent's tireless efforts to get them food had come to naught, while

his supplier was on the record as stating: "So far as I'm

concerned, if the Sioux are hungry let them eat grass or their own

dung."

In August, six

young warriors raided a farm in Acton, killing five white

settlers. From this incident violence spread like a prairie

fire throughout southwestern Minnesota. Before the uprising

could be contained more than 350 whites lay dead in the largest

massacre of whites, by Indians, in the nation's history.

Lincoln was so

fixated on Robert E. Lee's forays into Maryland that he had little

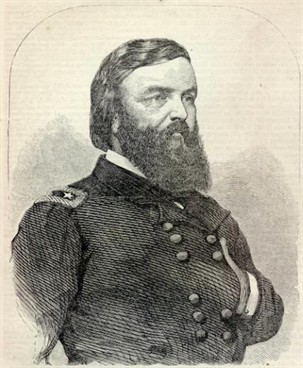

time for Indian affairs on the frontier. He sent General Pope

(below) - fresh from a humiliating defeat at the Second Bull Run,

to take charge of the situation, but Pope approached the assignment

with resentment and transferred his anger to the Sioux.

When he arrived in Wisconsin he found "panic everywhere," and

predicted an all out Indian War would break out unless the Indians

were severely punished. He announced to his troops that

his objective was to "utterly exterminate the Sioux if I have the

power to do so...and they are to be treated [by us] as maniacs or

wild beasts."

Minnesota

officials liked this man. Here was an opportunity to use

Pope's animosity toward the Indian to rid themselves of their red

neighbors and take ownership of all their lands. Pope's

command broke the back of the rebellion in October and a military

commission put more than 1,500 Indians on trial in a notorious

spectacle.

President

Lincoln was the first to admit that he was poorly informed on

Indian affairs. John Ross, the Cherokee chief, urged him to

offer military protection to the Cherokees who had fallen under

confederate control, but he dodged the challenge by replying that

he had his hands full with the war in other places. Like most

whites of the time, Lincoln regarded Indians as a barbarous race of

people who were obstacles to progress. When at their most

patronizing, Washington politicians enjoyed visits by Indians

chief. They brought color and exotic culture to the city,

where men like Lincoln spoke to them in pigeon English and

explained that the world 'is a great, round ball.'

click here for more

By early

November, Pope sent Lincoln a list of 303 Sioux men the military

court had found guilty and condemned to die. Lincoln ordered

complete transcripts of the trials, and after reading them (over

the protests of an indignant Pope), he commuted the sentences of

all but thirty-nine. When he heard of the commutations,

Senator Morton (Minn.) threatened Lincoln with an ultimatum:

"Either the Indians must be punished according to law, or they will

be murdered without law."

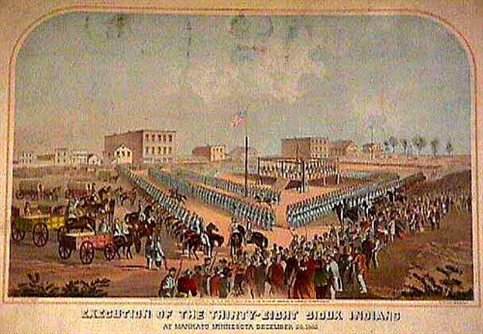

Thirty-eight Sioux were hanged at a public executiion in

Mankato, Minnesota

On December 26,

in the largest public execution in American history, thirty-eight

men swung from the gallows (one more had been pardoned at the last

moment). Lincoln's clemency of the others set off a firestorm

of rancor among whites that carried over into the next

election. Republicans lost strength in Minnesota in the

election of 1864, which took place the same month as the Sand Creek

Massacre in Colorado. Governor Ramsey admonished the

president that had he hanged more Indians he would have received a

much larger majority.

"I cannot

afford to hang men for votes," Lincoln replied.