To the Arapaho, Sioux, and

Cheyenne, it seemed as if the Great White Fathers now looked upon

Horse Creek as another worthless document signed by people who were

seen as nothing more than obstacles to the march of empire.

Like the treaties that preceded Horse Creek and all that were yet

to follow in the next twenty years, the ground-breaking agreement

forged between the Great White Fathers and the "wild and savage"

tribes of the American Plains could fulfill its promise through

rigid enforcement, but there is scant evidence to suggest that

Congress ever gave serious consideration to this aspect of

treaty-making. And no single event of that period would attest to

the solemn consequences of Washington's neglect more than the Sand

Creek massacre of December 29, 1864.

click

here for more

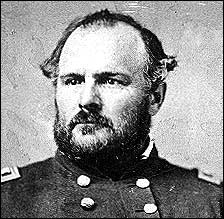

When he heard

that Chief Black Kettle's band of Cheyenne were settled into their

winter camp a few miles northeast of the frontier town of Denver, a

firebrand Methodist minister, Colonel John Chivington, led his

mounted command on a night-long march in search of the Indians.

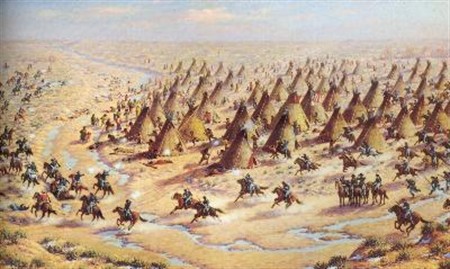

An artist's depiction of the Colorado milita's massacre

of Black Kettles band of Cheyenne women, children, and old people,

at Sand Creek in 1864. Soldiers paraded with babies impaled

on bayonettes, while others eviscerated the sexual organs of

murdered women and stretched them over their hats like ornamental

hat bands. "What we have learned about the Americans," said

Cherokee philosopher John Ross, "is that the perpetrator of these

crimes never forgives his victims."

click

here for more

Having recently

signed a new treaty of peace, Black Kettle had been promised

protection by the U.S. Army from other bands of Indians that were

trying to wrest away the Cheyenne hunting ground in eastern

Colorado. Black Kettle, whose camp of a hundred lodges was

made up of mostly women, children, and old people, had proclaimed

his neutrality in all the skirmishes being fought on the

countryside around his winter camp. With nothing to fear, the

members of his band lay peacefully asleep as dawn broke on a cold

winter morning.

When Black

Kettle stepped from his lodge and saw the frieze of blue coats

arrayed on the cut bank above the village, he quickly raised the

American flag on a standard to display his neutrality, but the

gesture was ignored. When Colonel Chivington was asked what they

should do about the women and children, he ordered his men to kill

them all. Then, he waved his saber in the air and ordered his

troops to open fire.

"Then the scene

of murder and barbarity began -- men, women, and children were

indiscriminately slaughtered," reads the report from Congress'

official investigation. "In a few minutes all the Indians

were flying over the plain in terror and confusion. A few who

endeavored to hide themselves under the bank of the creek were

surrounded and shot down in cold blood. From the sucking babe

to the old warrior, all who were overtaken were deliberately

murdered. Not content with killing women and children who

were incapable of offering any resistance, the soldiers indulged in

acts of barbarity of the most revolting character; such, it is to

be hoped, as never before disgraced the acts of men claiming to be

civilized. No attempt was made by the officers to restrain the

savage cruelty of the men under their command, but they stood by

and witnessed these acts without one word of reproof."

Congressional

investigators called Chivington's interpreter, John S. Smith, to

submit to cross examination before members of Congress.

Investigator: Were the women and children

slaughtered indiscriminately, or only so far as they were with the

warriors?

Smith: Indiscriminately.

Investigator: Were there any acts of barbarity

perpetrated there that came under your own observation?

Smith: I saw the bodies of those lying there cut

all to pieces, worse mutilated than any I ever saw before, the

women all cut to pieces.

Investigator: How cut?

Smith: With knives; scalped; their brains knocked

out; children two or three months old; all ages lying their, from

suckling infants up to warriors.

Investigator: Did you see it done?

Smith: Yes sir, I saw them fall.

When the guns fell

silent, after the screams and wails of the dying had fallen quiet

and the last crying babies had been run through with bayonets, the

sordid work of the troops commenced in earnest. As their

commander looked on from the bluff above the village, Chivington's

troops worked their way through the village from lodge to lodge,

lopping off ears and fingers as they went, and gathering ornaments

and scalps from the victim's bodies. Then came the signature

atrocity of this massacre, the dissection of the women's genitalia

with bayonets and Bowie knives. Commonly, the eviscerated

body parts were stretched over the soldier's caps and worn as

hatbands - the prized souvenirs of battle. When Chivington and his

men rode into Denver, they were welcomed by the governor and a

throng of citizens as conquering heroes, all hats bristling.

The God-fearing women of Denver then collected the scalps and

mutilated genitalia of the Cheyenne women and children and hung

them like a Christmas swag over the stage at the Denver opera

house.

The

government's investigation concluded: "As to Colonel Chivington,

your committee can hardly find fitting terms to describe his

conduct. Wearing the uniform of the United States, which

should be the emblem of justice and humanity…he deliberately

planned and executed a foul and dastardly massacre which would have

disgraced the veriest savage among those who were the victims of

his cruelty…and took advantage of their inapprehension and

defenseless condition to gratify the worst passions that ever

cursed the heart of man. Whatever may have been his motive, it is

to be hoped that the authority of this government will never again

be disgraced by acts such as he and those acting with him have been

guilty of committing."

Chivington and his men rode away from Sand Creek as bona fide

heroes in the eyes of their fellow Colorado citizens. Despite

the blistering verdict of congressional investigators, neither the

Methodist minister, nor any of his subordinates, was ever punished,

fined, or court marshaled for their deeds. The United States

government promised to compensate the Cheyenne and Arapaho for the

massacre committed at Sand Creek, but when the treaty reached the

Senate for ratification, the Select Committee on Indian Affairs

quietly deleted that provision. "Today, Indians remember that the

United States Army, led by a Methodist minister, ruthlessly

slaughtered nearly five hundred defenseless Indians," wrote the

late Sioux legal scholar, Vine Deloria Jr., in Utmost Good

Faith. "Before

there can be any warm feelings that we are all "one people," the

United States government must make compensation to the Cheyenne and

Arapahos for Sand Creek."

Related Events

Related Flashpoints

Related Places