In 1867, a peace commission

was dispatched by lawmakers in Washington to report on the

condition of the plains Indians. The commissioners,

including generals Harney and Terry, were assisted by Pierre

deSmet, and met with chief's Gall, Red Cloud, and Sitting Bull,

among many others.

click here for more

The

commissioners reported back to Congress, "Here our civilization

made its contract and guaranteed the rights of the weaker

party. We did not stand by those guarantees. The

treaties were broken, but not by the savage." In other words,

as treaty scholar Paul Prucha has written, "The treaty process had

developed into a "convenient and accepted vehicle for accomplishing

what United States officials wanted to do."

Pressures from

the Indian Office forced Congress to ratify the Medicine Lodge

treaties in 1867, but on July 27, 1868, Congress turned against the

peace commission. Appropriating $500k to implement the

treaties with the plains tribes, Congress specified that the funds

be spent under the direction of Sherman. In other words, said

historian S.J. Killoren, "Congress handed the Plains tribes over to

the army."

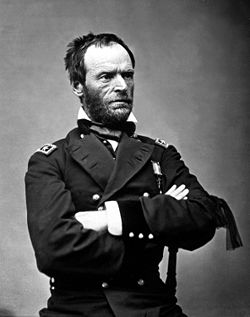

General

Sherman's (right) approach to managing the tribes was Big Stick

diplomacy coupled with threats of force. When a few Cheyenne

and Sioux went on the Smokey Hill trail, Sherman declared: "No

better time could possibly be chosen than the present for

destroying or humbling those bands that had so outrageously

violated their treaties and begun a desolating war without one

particle of provocation... I will solicit an order from the

President declaring all Indians who remain outside of their lawful

reservations to be declared 'outlaws,' and commanding all people -

soldiers and citizens - to proceed against them as such."

Sherman and

Sheridan agreed on a winter offensive, and "like Georgians and

Virginians four years earlier, the Cheyenne and Arapahos would

suffer total war." Sherman wrote to Sheridan that he had his

full support, and if the winter campaign "results in the utter

annihilation of these Indians, it is but the result of what they

have been warned again and

again."

Sherman's views

of Indian country were expressed in his annual report to Congress -

"they must necessarily yield," a haunting echo of President

Jackson's words spoken thirty years earlier. The peaceful

coexistence promised in the 1851 Horse Creek treaty was now viewed

as a pipe dream. President Grant's attitude toward Indians

was, in the beginning, very similar to Jackson's: "Even if it meant

the extermination of the race, the Great Plains were to be secured

for emigrants." But that attitude would change with his peace

commission.

By the fall of

1868, the peace commission was completely dysfunctional as a

governmental entity. Taylor, the president of the commission,

was faced with a mutiny. Nobody, including the president of

the U.S., wanted to promote a peace program.

Proposals of

Sherman, Harney, and Terry were carried over the dissenting votes

of Commissioner Taylor and Tappan. Sherman's policy of "peace

within the reservations, war without," were accepted strategies for

going forward. Before the commission adjourned Sherman

concluded his power sweep by resolving that Taylor, as spokesman

for their group, should transmit the commission's resolutions to

Grant, including the recommendation that "the Bureau of Indian

Affairs be transferred from the Interior Department to the War

Department."

Indian

Commissioner Taylor submitted his annual report with a searing

rejoinder of Sherman's last demand: "If you wish to exterminate the

race, pursue them with the ball and blade; if you please, massacre

them wholesale, as we sometimes have done; or, to make it cheap,

call them to a peaceful feast, and feed them on beef salted with

wolf bane; but, for humanity's sake, save them from the lingering

syphilitic poisons, so sure to be contracted about military

posts."

"The passing

through their country of a continuous stream of emigration,

dispersing or destroying the buffalo, is one of the causes of great

discontent and suffering with them," he went on. "Treated

thus, and no adequate compensation being made to them for what they

have yielded up or lost, their resources of subsistence and trade

diminished, with starvation in the future staring them in the face,

the wonder is that there prevails any degrees of forbearance on

their part, with such provocations to discontent and

retaliation."

Sherman instructed Sheridan to chase down the wandering tribes and

"prosecute the war with vindictive earnestness until they are

obliterated or beg for mercy." His orders were followed

by a young colonel named George Custer, who, almost four years to

the day after Sand Creek, wiped out Black Kettle's peaceful camp of

women, children, and old people, in a massacre at the Washita

River. The Indian Wars had begun.

Related People

Related Flashpoints