Indian removal was a simple

idea in the minds of southerners, but the practicalities of

relocating that many tribes to homelands thousands of miles away

was daunting and fraught with unintended consequences.

In many cases,

the land set aside for specific tribes was already occupied and

settled by whites. The local Indians had to agree to accept

reduced territories, and, in some cases, relocation, once

again. This was work that fell to Indian Superintendent

William Clark, in St. Louis, who was pushed by events beyond his

control to negotiate new treaties with the Kansas, Osages, Quapaws,

and others at the same time he was opening land west of Missouri

and Arkansas for eastern tribes.

The First Removal Era

in the east flowed without interruption into the Second Removal

Era, which displaced western tribes from treaty protected

homelands. The Third Removal Era began in the 1950s, when

Congress attempted to force Indians off their home reservations

with threats of terminating tribal governments, with forced

relocation programs, and by condemning their homelands under

eminent domain in order to build massive flood control dams on the

Missouri River. it is important to note that each of these

removal eras was eventually ruled unlawful by the U.S. Supreme

Court, or by Congress itself. These repeated and devastating

forced relocations have left deep scars of resentment and distrust

in the relations between tribal governments and non-Indian

people.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indian_removal

But many of the eastern tribes were

still very reluctant to move. Congress and

President Jackson ignored imperatives of nature (not to mention

their legal obligations), and the Indians opposition. Tribal

leaders urged Jackson to obey the dictates of the high court, which

ruled against removal, but knowing that Justice Marshall had no way

to enforce his decisions, Jackson pressed ahead with removal over

the court's objections. At this point, Jackson's

failure, ne, his refusal to fulfill his constitutional obligations

to the tribes destroyed what resolve they had left. Now, many

Indians abandoned their resolve to stand and fight and began moving

West.

Factions of Cherokee, Creek,

and Seminole's refused to emigrate. Despite Jackson's empty

words to Congress that emigration "should be voluntary for it would

be as cruel as it was unjust to compel the aborigines to abandon

the graves of their fathers," he sent federal and state troops to

round up the recalcitrant Indians and set them off on forced

marches under military guards.

The resulting 'trails of

tears' rank with the great tragedies of the ages. Although

federal officials were responsible for supervising the removal,

private contractors were hired to supply rations and

transportation, with disastrous results. The Cherokee, for

example, were caught on the overland trail in midwinter, enduring

freezing temperatures, snow, ice storms, and sudden thaws that

bogged down the pack trains in knee-deep mud. If these

conditions weren't enough misery, add to them rations of spoiled

meat, corn, and flour supplied by the disreputable

contractors. The tribes on the trail lost one fourth of

their people.

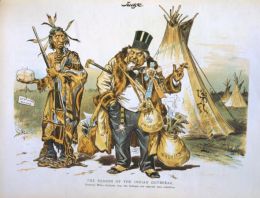

The survivors

claimed that the suffering and deaths were due to the callousness

of the contractors, whom, they said, had used the plight of the

Indians to line their own coffers. The anger over

charges of profiteering and fraud was so fierce that officials in

Washington hired Major Ethan Allen Hitchcock to investigate the

complaints. An investigator for the Smithsonian Institution's

Bureau of American Technology, John R. Swanton, applauded the

appointment: "Since…the national administration was willing to look

the other way while this criminal operation was in progress, it

made a curious blunder in permitting the injection into such a

situation of an investigator as little disposed to whitewash as was

Ethan Allen Hitchcock."

Hitchcocks's

investigation commenced in November, 1841. Soon, the cautious

but fearless Hitchcock found that "bribery, perjury, and forgery,

short weights, issues of spoiled meat and grain, and every

conceivable subterfuge, was employed by designing white men on

ignorant Indians."

Hitchcock's

report, along with one hundred exhibits, was filed with the

secretary of war. Committees of Congress demanded the right

to review the material, but the findings in the report were so

scandalous, said Swanton, that the secretary of war refused to make

it public, and "…its mysterious disappearance from all

official files proves at one and the same time the honesty of the

report and the dishonesty of the national administration of the

period."

Related People

Related Events

Related Flashpoints

Related Places