In a letter to the governor of Virginia,

President Jefferson wrote: "However our present interests may

restrain us within our own limits, it is impossible not to look

forward to distant times, when our rapid multiplication will expand

itself beyond those limits and cover the whole northern, if not

southern continent, with a people speaking the same language,

governed in similar forms and by similar laws."

click here for more

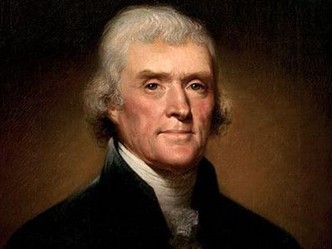

Thomas Jefferson, a man who

never traveled more than 20 miles west of his home, Monticello, in

Virginia, was among the first to dream of moving the national

borders to the Pacific Ocean.

In part, the impetus to empire

and exploration came from the fact that no one really knew what was

out there, and no one was more curious than Thomas Jefferson.

It is sometimes said that Europe invented the Enlightenment and the

United States installed it on the Lockean tabula rasa of

the West. Like many of his ideas, Jefferson, the historical

figure, is a paradox. He had an expansive imagination but a

very limited knowledge of the West. He never travelled over

the Appalachian Mountains, so perhaps experiencing it in his

imagination set his mind free from the sobering considerations that

confronted the explorer. He was free to conceive of the

unimaginable in an open landscape, with nothing to loose and

everything to gain from his wanderings.

Jefferson may

have been intentionally crafty and evasive in public about the

Louisiana Purchase, but he intended for Lewis and Clark to make it

very clear to the tribes they met that they met along the way that

they were now residents of the United States and that the Great

White Fathers fully intended to control trade in the West. In

truth, Lewis and Clark were poorly prepared to negotiate the

complex political network of trade and blood-alliances that had

evolved on the plains over the course of many centuries. What

Lewis saw was the "unsteady movements and tottering fortunes" of

Indian people as measured through the eyes of someone shaped by the

gentrified upper class lifestyle of colonial Virginia, so it is not

an accident that the these first attempts to bring Indians into the

fold were generally unsuccessful.

To say

Americans discovered the southwest is presumptuous. When the

first American explorers set out in the nineteenth century from St.

Louis, bound for Santa Fe and Taos, they were venturing into a

region that had been the scene of extraordinary feats of discovery

by Spaniards for nearly three hundred years. Creaking and clanking

in their suits of metal, Spanish conquistadores and their

ferociously devout Jesuit missionaries had criss-crossed the region

from the Texas coast to the San Joaquin Valley and the coastal

plain of southern California. Garcia Lopez de Cardenas was

the first European to behold the Grand Canyon, almost three hundred

years before an American citizen would venture into its forbidding

canyons.

By 1776, American colonists

had barely ventured past the ridge back of the Appalachian

Mountains, but the Spanish knew about the seemingly endless

grasslands first traversed by Coronado two hundred years and fifty

years earlier. In 1809, based on information compiled

from the notes and journals of Spanish explorers, the great

naturalist Alexander Von Humbolt published his monumental map

entitled 'Map of New Spain,' detailing the southern coastline from

Florida to the Baja.

Click here for more

Related People

Related Events

Related Places