John Augustus Sutter, an

entrepreneur's entrepreneur, created an empire for himself in

California after coming to America from Switzerland, but he was not

satisfied with his empire. (click here for more)

The Sacramento valley had given

Sutter a fresh start after a series of business failures in

Switzerland. After crossing the continent with one of

Fitzpatrick's wagon trains, Sutter had built a small empire of

50,000 acres of land, orchards, a trading post and a fort, all on

the present day site of the California state capitol.

What he needed now was a sawmill to produce lumber that could turn

more of his dreams into real things.

On Friday,

August 27, 1847, Sutter noted in his journal that he "made contract

and entered in partnership with James Marshall for a sawmill to be

built on the American fork." James Marshall, an amateur

millwright from Hope Township, New Jersey, set off with his

business partner, John Wimmer, to build Sutter a sawmill on the

American River, forty-five miles from his trading post on the

Sacramento River.

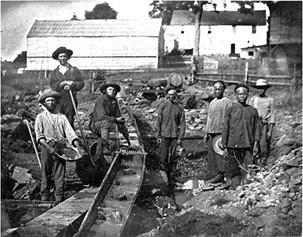

Forty-niners working a placer claim in the California gold

fields of the Sierra Nevada mountains.

On the morning of

January 19, 1848, Marshall was checking the millrace driving the

water wheel that powered the mill. Something shiny in the

bottom of the ditch caught his eye. "I reached my hand

down and picked it up; it made my

heart thump, for I was certain it was gold." The nugget he

found was the size of a small pea. This moment of private

astonishment would change the course of history. Marshall had

discovered gold on the south fork of the American River in

California. (In the end, he never made a cent on his

discovery.)

Sutter tried to keep a lid on the

news, but his efforts were no match for the lure of gold. As

Marshall and Sutter were waiting for the official assay, Marshall's

men were finding more nuggets at the site of the millrace, and it

wasn't long before other Californians got wind of the rumor (for

more on the 49'ers, click here).

The discovery

of gold in California, and the opening of the overland trail, were

two events that brought the Brule and Oglala Sioux into close

contact with a class of white people that was unlike any they had

previously met. With fur traders they shared many interests,

but with the gold diggers and agrarian settlers they had little in

common. These people hurried along the trail and

managed to devastate everything they touched, including grasslands

and rivers, streams and stands of timber.

By April of

1849, 30,000 Americans had set out for the California gold

fields by land. Twenty-five thousand more left by

clipper ships rounding Cape Horn. "Passengers on the clippers were

fed like hogs," wrote one gold seeker. The biscuits served to

passengers, wrote one landlubber, "were invested with black bugs

burrowing into it like woodchucks in a sand bank."

Others would

sail to Panama, transit the isthmus by foot, and hope to catch a

coastal steamer for the last leg up the west coast to

California.

It seemed the

entire nation was on the move, and many were on their way to

California, a development that terrified the California

Indians. The 1849 massacre of 130 Pomo men, women and

children who were fishing peacefully on a lake, was just the

beginning of the atrocities that would kill five in six California

Indians between 1850 and 1860. Whites declared open season on

California Indians and did not even attempt to stay within the

law.

Related People

Related Events

Related Flashpoints