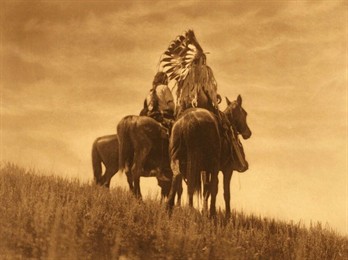

What the Founders of the American republic could not have

forseen was the manner in which the success or failure of "National

expansion' to the Pacific Ocean in the 19th century would depend

almost entirely on one legal tool - the Indian treaty.

The unlawful removal of Indians from their treaty-protected

homelands in the nation's southern states in the 1820s and 1830s

hurled the nation into a fiercely contested feud that pitted states

against the federal government over the question of Native American

sovereignty. When the nation's highest court ruled that the

states did not have dominion over Indian governments, President

Andrew Jackson and the legislatures of southern states ignored the

ruling and pressed ahead with their plans to forcibly remove

Indians from their homelands.

Probably no event in American history is more symbolic of the

American people's refusal to abide by their own laws of 'life,

liberty, and the pursuit of happiness,' or to honor their own

solemn promises made in treaties, than the events that led to the

Battle of the Little Big Horn. Here, the famed western artist

Charles M. Russell chose to focus on the Indian's attack rather

than the more common view of the 7th Cavalry's defense.

To expand westward, the American republic was legally obligated

to enter into hundreds of treaties with the Indian nations that

owned the land white citizens coveted from the nation's earliest

days. Those treaties were like stepping stones across

the continent, but in time, virtually everyone would be unlawfully

abrogated by the very lawmakers who ratified them.

The founding principles enshrined in the Declaration of

Indepence - life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness - were

denied to Native Americans, African Americans, Mexican Americans,

and Asian Americans, until well into the 20th century. Laws

passed in the 1870s denied Indians the freedom to practice their

own religions or to assemble without approval of government

agents.

Ethnographers estimate that the population of the America's in

1491 may have been as high as seventy-five million people. By

1900, the national census showed that fewer than a quarter of a

million Native Americans had survived the arrival of the European

in North America.

Many of the the battles during the Indian Wars of the 19th

century were started by white settlers ignoring the treaty rights

of Indians, conflicts that were further enflamed when the federal

government refused to defend Indian lands from whites as they had

promised in the treaty negotiations.

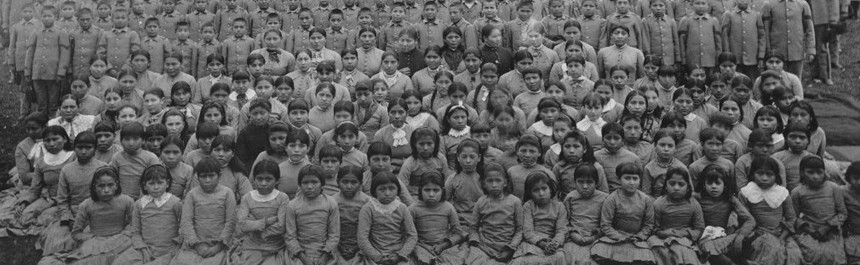

After the Dawes Act was passed in 1887, Congress ignored the

'establishment clause' separating church from state and turned

federal Indian policy over to Christian missionaries. For the

next fifty years, Indian children were abducted from their homes on

Indian reservations by Christian missionaries and federal agents

and taken to schools thousands of miles away where it was hoped

education in the white man's world would assimilate native people

into mainstream society. Thousands of Indian children died at

the schools, or disappeared after running away and trying to find

their way back home. Here, Indian children pose for a group

portrait at the Carlisle Indian School in Pennsylvania.

When Congress was negotiating the Kansas/Nebraska Act in the

early 1850s, it came as an enormous surprise to most lawmakers that

the United States had actually 'purchased' very little land - about

sixty square miles - when Thomas Jefferson and Napoleon Bonaparte

negotiated the treaty in 1803. For its $15 millon, the United

States purchased the right to govern the former French territories,

to move its national boundary to the Rocky Mountains and the

Canadian border, and to use the rivers for commerce. The

ratified treaty recognized the Indians of the West as the actual

owner of the land - an obstacle to 'national expansion' that could

only be overcome by negotiating hundreds of new treaties with

Indian nations.

Eminent domain, the law most commonly used by Congress in the

third removal era to condemn Indian lands in order to build massive

flood control dams on major rivers in the West, was first invented

by Crusade Era popes to justify the confiscation of lands owned by

'saracens and infidels' in the Holy Lands. That law, once it

found its way to the New World, was incorporated into the founding

charter of the United States.

The federal government's first 'treaty of friendship' was signed

with the Delaware Indians in 1778, and the last, with the Nez

Perce, was ratified by the U.S. Senate in 1871. By then, the

federal government had entered into more than 370 solemn compacts

that were protected by Article VI of the Constitution as 'the

supreme law of the land.' National expansion beyond the

original 13 states would have been difficult to impossible without

treaties which formed stepping stones across the contient to the

Pacific Ocean. As time went on, government officials showed

little inclination to fulfill the government's obligations to the

Indian nations once white settlers had taken possession of the

Indians' lands.

The first 'Indian removal era' began in the 1820s and ended with

the Trail of Tears. The second removal era commenced in the

1860s and ended when western Indians had been forced onto

reservations. The third began in the 1940s when Congress

condemned Indian trust lands to make way for hydroelectric dams on

major western rivers. Here, George Gillette of the Mandan,

Hidatsa and Arikara nations, breaks into tears as Secretary of the

Interior Krug signs the official 'takings' documents that would

condemn 150,000 acres of tibal lands and destroy nine Indian towns

and thousands of home on the upper Missouri River. All three

removal eras have since been ruled 'unconstitutional' by the U.S.

Supreme Court.

From our earliest beginnings as a republic,

long before the American colonists won independence from the king

of England, men and women dreamed of building a nation of laws that

safeguarded basic, inalienable rights for all citizens. In

the early 18th century this idea - a nation of laws - was a radical

departure from the autocratic governments that had ruled the people

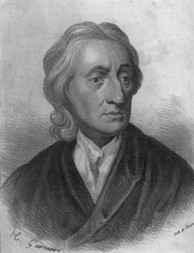

of Europe for nearly two thousand years. To build a

nation of laws, wrote the 17th century English empiricist, John

Locke (the ideological midwife of our Declaration of Independence),

is the natural aspiration of all free men.

When our Founders were presented

with the opportunity to build just such a nation, they erected the

American house of democracy upon a hierarchy of laws. Some

laws - the load bearing beams that support the floors and roof -

have to carry more weight than the joists and rafters.

These structural laws protect our most sacred principles - that all

men are created equally in the eyes of the law and have inherent

rights to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness (and

property). They are enumerated in the first ten amendments to

the U.S. Constitution, also know as the people's Bill of

Rights. Joining those laws is a keystone construct that the

Founders called 'the supreme law of the land.' This keystone

construct gives the central government the power to make treaties

in sovereign-to-sovereign compacts.

Bundled together in the

complex framework of the U.S. Constitution are the laws that carry

forward the hopes and dreams of United States citizens from one

generation to the next. The Constitution also makes it

possible for our nation to co-exist peacefully (and to resolve

conflicts) within the larger community of nations. At the

other end of this spectrum of laws are those laws not embodied in

the Constitution - laws, for example, that tell us how fast we can

drive a car, that yelling 'Fire!' in a crowded theater is not

protected under the freedom of speech, or how much it costs to

license a pet.

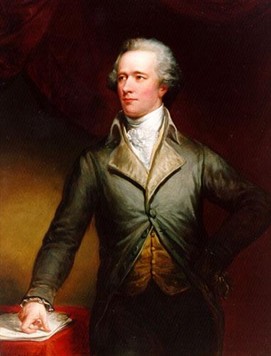

We

might ask, as Alexander Hamilton asks in Federalist Papers, "Why

has government been instituted at all?" All of human history

makes that answer rather obvious, says Hamilton. We have

instituted government because the history of human societies has

taught us that "the passions of men will not conform to the

dictates of reason and justice without constraint." Thomas

Jefferson and his cohorts disagreed with this assessment.

They argued that free men, left to their own devices and

opportunities, would always act in an altruistic fashion that

benefited their neighbors, and society in general. Hamilton

scoffed at this notion and accused Jefferson of being completely

ignorant of 'the science of human nature.' The tension that existed

between these views at the very beginning of our nation is the same

tension that has charged the mainspring of democracy with its

vibrancy and energy, ever since. Such disagreements are both

the strength of democracy, and its Achilles heel.

Hamilton - the one true genius among a multitude of near deities we

call our Founders - had summarized human history in a few

words: government is necessary because the passions of men will not

conform to the dictates of reason and justice without

constraint. Joseph Ellis, one of George Washington's recent

biographers, tells us that Washington agreed. The nation's

First Citizen saw deep and worrisome fault lines running through

our national character. From our earliest rumblings as a

nation, he and Benjamin Franklin were deeply worried that "Life,

liberty and the pursuit of happiness," the most cherished

principles of American democracy, would be denied to the very

people who made 'national expansion' possible -- the Native

Americans. With mounting dread, Washington recognized that

"what was politically essential for a viable American nation was

ideologically at odds with that it claimed to stand for." He

and Ben Franklin (among others) realized the United States was

shaped at its moment of conception by antipodal ideals and

underlying paradoxes. Somewhere on the way to full national

maturity there would have to be a reckoning between what was

'politically essential' for national survival, and what the nation

claimed to stand for - the principles enshrined in it's laws.

On the road to

nationhood, the Founders elevated the government's treaty-making

powers to the 'supreme law of the land' in order to prevent

individual states from negotiating separate treaties with sovereign

Indian nations. As important as this provision was to

the integrity of the national government, the Founders had laid

claim to an exclusive privilege that would fuel all future battles

over federalism (the distribution of power among competing

governments). As Chief Justice John Marshall later explained

in several important Indian cases, the U.S. Constitution was

a flawed document of incorporation. Chief among those flaws

was the Founders' failure

to explain how sovereign Indian nations would fit into the scheme

of federalism that incorporated many state governments within one

national government. As we now know, this flaw in the

national charter would account for untold misery, bloodshed, and

the 'genocide' of Indian people throughout the nation's first

century.

failure

to explain how sovereign Indian nations would fit into the scheme

of federalism that incorporated many state governments within one

national government. As we now know, this flaw in the

national charter would account for untold misery, bloodshed, and

the 'genocide' of Indian people throughout the nation's first

century.

Without the supremacy clause, without

the power to make treaties with sovereign nations (Article VI of

the Constitution), the tiny republic of thirteen states on the

eastern seaboard could never have expanded beyond the Appalachian

ridgeline. The 'supremacy clause' in Article VI of the

Constitution put the federal government, and the leaders of Indian

nations, on an equal legal footing in sovereign-to-sovereign

negotiations over Indian owned lands and resources. As

restless citizens looked west to establish new settlements in the

Ohio Valley, the first casualties of national expansion would be

the nation's most sacred laws. Just as Washington had

feared, the vanguard of white society trampled the native's

inherent sovereignty and freedom with grave consequences for the

nation's most sacred principles: 'life, liberty, and the pursuit of

happiness.' The first society to build itself into nation of

laws was also the first to violate those laws in the name of

national expansion. Eastern tribes were the first to

experience a new truth about the republic of laws and its legal

system: the values of liberty and equality in America were

contingent on whose liberty and equality were at stake in all

contests over land and resources.

When the United States was founded in

1787, it came into existence inside the much larger boundaries of

Native America. Over the next hundred years, land cessions

made in hundreds of treaties by 500 Indian nations, and ratified by

the U. S. Senate, allowed the westward-looking Americans to expand

across the continent to the Pacific Ocean. To our national

misfortune, generations of American school children have been

taught a simplistic thesis of expansion put forward by historian

Fredrick Jackson Turner more than a century ago; that the plotline

of the nation's story followed the frontier west to the Pacific

Ocean. Here, we argue that Turner's frontier thesis is an

earnest but simplistic subplot to a much larger narrative that

better explains the century-long phenomenon we call 'national

expansion.'

Instead

of constructing our national story by following frontier

settlements across the continent, as Turner recommends, we argue

that the story of the nation's laws, and the story of how those

laws shaped the hundreds of treaties we made with sovereign Indian

nations, creates a much more compelling and accurate account of how

Americans accomplished 'national expansion' to the Pacific Ocean in

the 19th century. This reinterpretation explains 'how' and

'why' the hundreds of treaties with Indian nations make a precise

and faithful model for our national story.

Our story of

'national expansion' begins with the signing of the first treaty of

friendship with the Delawares, in 1778, and ends over a

century later when the census of 1900 showed that a robust

civilization of many millions of native people had been reduced to

fewer than 250,000 in less than two centuries. This model

also demostrates how George Washington and Benjamin Franklin's

fears became the history of record that we share today with Native

Americans (African Americans, Latinos, and Asian Americans).

On our path to full national maturity, the historical record makes

it clear that we abandoned our most sacred laws in order to lay

claim millions of square miles of land owned by sovereign Indian

nations.

Seen through the

parallel lenses of history and law, 20/20 hindsight explains how

Indian treaties became society's stepping-stones across the

continent. In steady and methodical fashion, settlers moved

across the eastern wilderness owned by the Five Civilized Tribes

and the Iroquois Confederacy, the Sauk and Foxes and Miami and

Delaware, among others, and jumped across the Mississippi River

where they made treaties for land cessions with tribes in Arkansas,

Missouri, and Iowa, before forcing them, too, off their

lands. As the Second Era of treaty-making began in 1850,

settlers crossed the Indian land bridge between Independence,

Missouri, and the Willamette Valley of Oregon, and devastated

Indian lands and resources. They pushed their settlements

across a Great Plains owned by the Mandan, Hidatsa, Arikara, Sioux,

Pawnee, Kiowa, Comanche, and Assiniboine, where they turned the

prairie into rectangular homesteads before mounting an assault on

the Rocky Mountains of the Shoshone, Crow, Blackfeet, Nez Perce,

Cheyenne, and Flathead.  Treaties they made with

mountain and river tribes carried them to the Pacific Ocean.

Once there, treaties of peace with dozens of coastal tribes, such

as the Modoc, the Cahuilla, Salish, and Snohomish, among others,

were abrogated almost as quickly as gold prospectors, settlers, and

fur traders, turned the ceremonies of peace into a record of

national dishonor. Only one in six California Indians

survived the golden state's the first decade of statehood.

Treaties they made with

mountain and river tribes carried them to the Pacific Ocean.

Once there, treaties of peace with dozens of coastal tribes, such

as the Modoc, the Cahuilla, Salish, and Snohomish, among others,

were abrogated almost as quickly as gold prospectors, settlers, and

fur traders, turned the ceremonies of peace into a record of

national dishonor. Only one in six California Indians

survived the golden state's the first decade of statehood.

As the

preeminent legal scholar, historian, and author, Charles Wilkinson,

has written, "This is the true story of the era of Manifest

Destiny and the westward expansion." This is America's story,

our story - the enduring legacy of the paradox of freedom

that is yours, mine, ours, and the birthright of all who will

follow us. This web site seeks to support the film and the

book with materials and resources that provide essential context

for the extraordinary role that treaties, and Native American

nations, played in the making of this nation. The History

Wheel, the hub of this site, integrates a multitude of sources,

events, people, and places, into a (hopefully) coherent,

multifaceted picture of how our nation was made. Ours is an

epic tale of popes and kings, presidents and rogues and savages and

scoundrels, a national narrative that is written in the blood of

the best and worst of us, on the timeless dust of this land.